Cusco 2C/Urbinsight project participants highlight transformative power of Peer-to-Peer Urbanism

As composting modules are sprouting up throughout Cusco’s historic neighborhoods and new archetype maps are being made available to planners, academics, and community members as a result of the Ecocity Builders-facilitated Secondary Cities (2C) pilot, Team Urbinsight thought it would be the perfect time to follow up with some of the people involved in the project.

To get a sense of how the experience has affected their thinking and collect feedback on how all the new tools and insights from the EcoCompass training program might be used to scale up and replicate the types of citizen-led holistic interventions that they helped co-create, we talked to four participants whose diverse perspectives from different civic sectors help to paint an overall picture of the pilot’s accomplishments so far.

Below are some of the snippets our intrepid reporter team of Sydney Moss, Joshua Castro, and Steven Bercu picked up as they visited with Community Participant Virginia Mendigure Sarmiento, Academic Lead Santos Mera, City Manager Abel Gallegos, and Ecocity Design Advisor Stephanie Weyer. It is by no means the definitive or exclusive guide to successful Peer-to-Peer Urbanism, but we hope it can provide a good window into what on-the-ground progress can look like at the completion of a pilot’s knowledge sharing and implementation phases.

Team Urbinsight meeting at Cusco’s office of land use planning (Ordenamiento Territorial). Left to right: Stephanie Weyer, Kirstin Miller, Abel Gallegos, Percy Rojas, Sydney Moss, Santos Mera.

1. Community Participant: Virginia Mendigure Sarmiento

When Sydney and Joshua went to follow up with the San Pedro resident about her experiences with the 2C/Urbinsight project, it was no surprise that Virginia took them straight to her back yard. There she demonstrated the composting module she had built together with her neighbors, a design based on the findings from data collected during the neighborhood waste audits. Showing off her compost-enriched soil and thriving plants, she shared her thoughts on the impact the project has had on her and her neighbors.

Virginia showing her compost bin to Sydney.

“This project is very interesting, because it teaches us how to take care of nature. Our ancestors, the Incas, used the composting method a lot, but unfortunately it was forgotten. So to reclaim that knowledge and take care of nature again is very gratifying and inspiring.”

Virginia pointed out that her concern about climate change had already better attuned her to the natural cycles, but the project presented a unique opportunity to actually do something about it by turning her own land into a showcase for regenerative practices.

“My goal is to ultimately bring all my neighbors here, to show them, motivate them, and to make it something big, at least in all the local neighborhoods.”

While she’s poised to help replicate the success of her own composting operation in as many Cusco households and neighborhoods as possible, Virginia also noted that for a large scale transformation of resource management to take place, engaged citizens need the support of their local government.

“One of the objectives of this project is to work with the provincial municipality to ultimately insert it into an ongoing process of participatory planning. With the proof of concept we now have, the only thing we need is the political will to raise environmental awareness among aspiring civil servants and for that awareness to turn into policy at the town hall level.”

She is convinced that this kind of focus on education is the most cost effective way to deal with Cusco’s mounting garbage problem in the long term.

“In order to scale up composting and recycling in the communities, authorities have to do more than just tell people to stop throwing away and start sorting their trash. They have to help them understand that these practices also improve the conditions of our planet.”

Community participants co-designing home composting modules.

2. Academic Lead: Santos Mera

As a teacher of environmental engineering at Universidad Alas Peruanas (UAP), Santos had already been working with Secondary Cities on material flow models for Cusco, so the partnership with Ecocity Builders to further build out the Urbinsight platform with all its potential for mapping and visualizing complex material flows through Urban Metabolism Information Systems (UMIS) presented itself as the perfect fit. When Joshua visited him on campus in June, he was eager to reflect on the breakthrough opportunities in data collection and organization the platform and its cutting edge methods had afforded him and his research team.

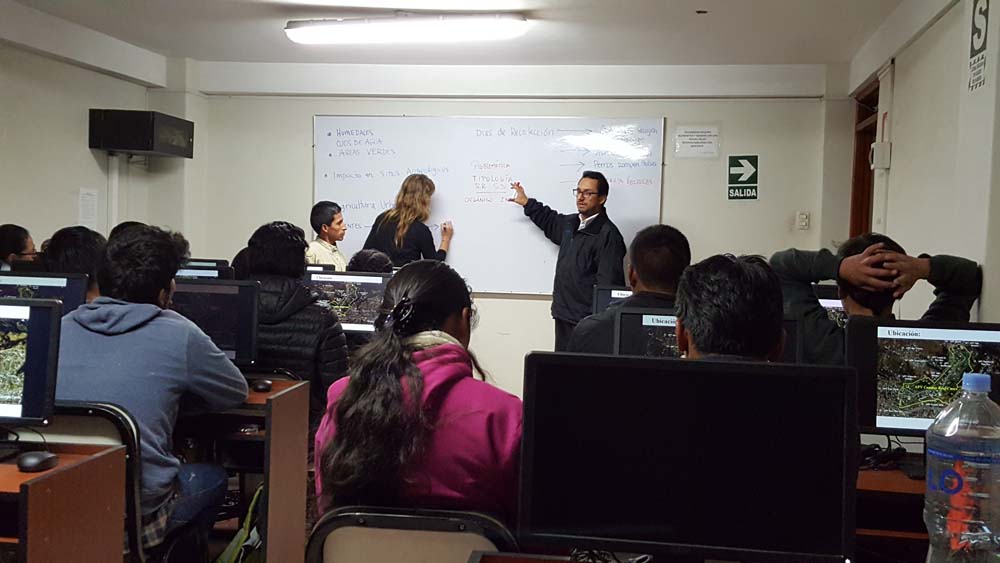

Santos and Sydney leading a Phase 2 workshop.

According to Santos, a big challenge the City of Cusco faces in dealing with its garbage crisis is that existing government stats are often superficial, unclear, and outdated, with quantitative information hard to come by. “One of the problems that we have in our country is that there is commonly a lack of first-hand information,” he said. “Researchers in this field don’t have a direct source from the state that could tell us how much is produced, what materials are used, and where things come from.”

Santos pointed out that being able to work with the neighborhood level material flow data generated by the EcoCompass training program’s household audits and environmental surveys is just one of the benefits of Urbinsight’s peer-to-peer process, albeit an important one. A less measurable yet perhaps even more valuable asset of the participatory method is the synergy generated between three stakeholders that are wont to pass by each other unnoticed in more conventional approaches to urban planning. “Here we have citizens who know about local problems, needs, and information gaps collaborating with academics who can help with the research and put together a proposal, which is reviewed, refined and approved by city managers who have been connected to the communities and the research from the get go.”

The data Santos and his interns gathered through the project showed that in 2016 San Pedro alone produced a ton and a quarter of solid waste. “Approximately 50% of that solid waste was organic, and when you add the 33% that comprise plastics, cardboard, and paper, you’ve got a whopping 83% of solid waste that shouldn’t end up in a landfill or be otherwise dumped.”

As a result of last year’s findings, Santos was able to get a compost research pilot funded for his interns this year. “This is just the beginning. Thanks to the success of the Urbinsight pilot we’ll be able to get support for and sustain future projects.”

Santos Mera (right) and his UAP student research team.

3. City Representative: Abel Gallegos

An architect by trade, Abel is the assistant manager at Cusco’s regional department of land use planning. When Joshua caught up with him at his office, he had a lot of good things to say about the city’s experience with the Urbinsight tools and methods.

“It was completely gratifying to collaborate with Ecocity Builders,” Abel summarized the experience. “They gave us interesting alternatives and tools to share information and build capacity with our citizens around indicators important to the construction of a more sustainable and resilient city.”

Abel (left) scoping conditions in the field with Santos.

What makes the ecocity concept uniquely valuable to Abel is its capacity to integrate broader underlying parameters like ecosystems or climate change into city management. Coupled with the first-hand collection of environmental data, this holistic approach equips planners like him with the tools to relate key indicators like water and waste to citizens’ quality of life.

Through the exchanges between the participants during the early phase of the project it became clear that waste and its management was not only of primary concern to the local communities but to the city. Consequently, getting the kind of detailed data from neighborhood waste audits about how and where waste is generated (collected and mapped out by Santos Mera and his student team in collaboration with the community participants!) enabled the city to make informed decisions on where to direct its resources.

“A fundamental outcome of the surveys was to focus our interventions on separation of materials, because that allows us to determine where to reduce, where to reuse, and where to recycle. And knowing that 50% of our total stream is organic made composting into the highest impact intervention to optimize the city’s solid waste management.”

Working with two distinct pilot neighborhoods turned out to be another important asset for the city. Gaining detailed information about the material flows of both San Pedro and Camino Real enabled Abel and his colleagues to establish two different neighborhood archetypes.

“The pilots we selected in Cusco are representative of the city and will help us to understand the city as a whole. That’s why the Ecocity Builders approach and methodology is so useful — it lends itself to replicability that can eventually be applied throughout the entire city.”

Sydney, Abel and Santos mapping out the neighborhoods.

4. Ecocity Design Advisor: Stephanie Weyer

To get the scoop about Urbinsight Cusco from the person who had been the most intimately involved in its day-to-day operations on the Ecocity Builders end, we had to recruit Board President Steve Bercu as our East Coast correspondent. After a 10 month stint in Cusco from January to October 2017 as design advisor for the project, Stephanie had just returned to Boston where she met with Steve to share her impressions.

Stephanie helping to construct compost models.

“It was just a unique opportunity to get to work with a community in a really close way on a project that we were definitely building something out of,” Stephanie replied when asked about what attracted her to the project when she first met Ecocity Builders Executive Director Kirstin Miller. “And Kirstin was open to me helping out.”

Arriving in Cusco just as the knowledge sharing phase of the project was moving into the implementation phase, Stephanie was immediately struck by the enthusiasm of the students and community members who were poised to construct the compost modules which they viewed as a solution for their city’s waste problems.

“These students did so much work! We walked around, went to all these different stores, negotiating with different people all the time to make this happen. And the communities allowed us into their homes. They let us borrow their tools!”

Stephanie said that as a landscape architect, it was interesting to learn where municipal resources come from and what they’re being used for, but also how to create resource loops in people’s own homes, which was the objective of the compost project.

“We talked a lot about close loop systems and resource supply issues in Cusco and other cities. With the project’s particular focus on waste, it was interesting to consider where Cusco’s food and resources come from and where it goes.”

Within a week of using the 17 composting models their pilot group had built, community members were reducing the waste that would previously have ended up in the streets by 95 kilograms (about 200lbs).

“The community was really excited that we had gotten this actual benefit,” Stephanie recalled. “It was measurable. We could actually envision to keep going with it.”

Community members and students with their final team report, including Virginia Mendivil (2nd from left, top), Stephanie Weyer (3rd from left, bottom, holding report), and Santos Mera (bottom right)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.