The Urban Metabolism of Brussels, Belgium: Transitioning Towards a More Circular Economy

Like many European and North American cities, Brussels is heavily dependent on energy, water and materials sourced elsewhere. While its metropolitan region — covering around 160 square kilometers and home to over 1.1 million inhabitants — has seen strong growth in consumption across most sectors in the last 40 years, its metabolism has remained mostly linear, meaning its resources flow through the urban system without much reuse, recycling, or other diversions and loops.

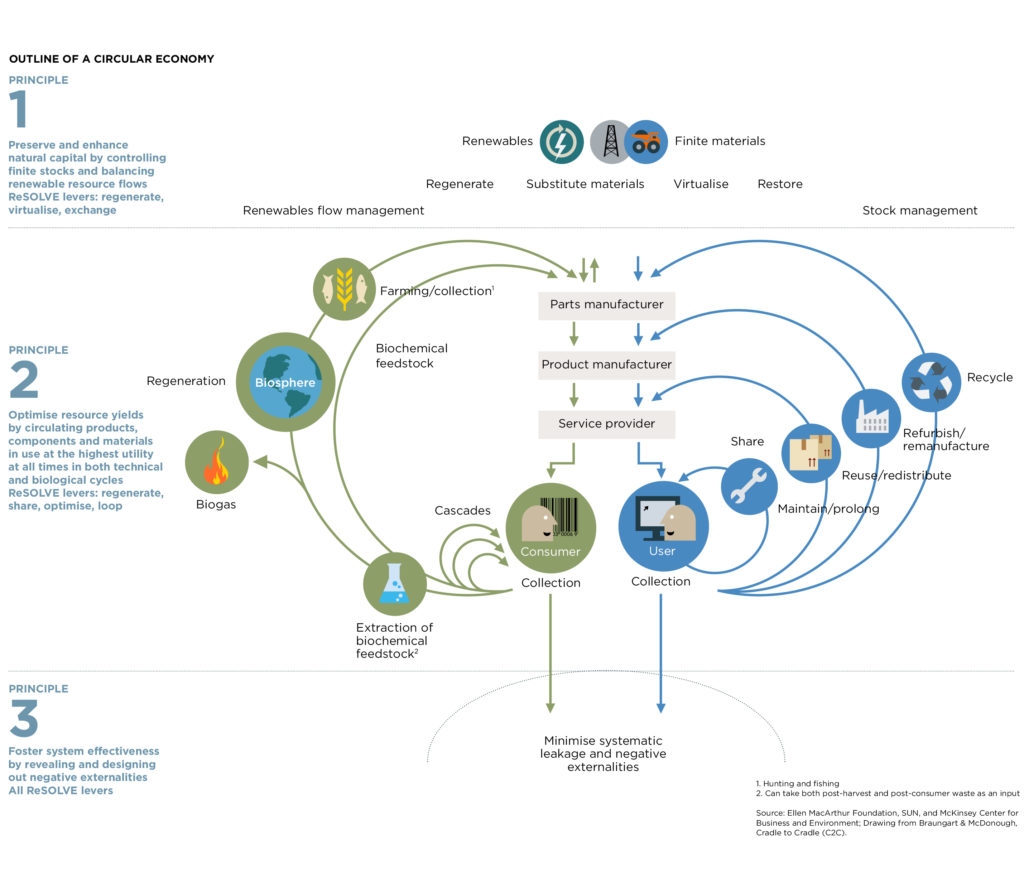

Lacking an economic and manufacturing base that could turn the imported overflow into valuable secondary materials, a commonsense approach to address these interrelated conditions at the core of its linear urban metabolism was to combine the region’s mitigation and reduction of its ecological footprint with the creation of new local jobs. Convinced that an economic framework outside of the predominant modern industrial cradle-to-grave model would be better suited to balance and mutually enhance these sometimes conflicting aspects, the Brussels Capital Region (CPR) adopted its Circular Economy Plan.

The plan, co-led by Brussels Environment, Impulse, Innoviris and Bruxelles Propreté and adopted in 2015, calls for facilitating the region’s transition to a more circular economy over a 10 year period, setting an example for innovation and development on the topics of circular economy and the efficient management of resources across Europe. To help Brussels shift towards a more circular economic state, Brussels Environment commissioned a Metabolism of the Brussels Capital Region that reviewed all existing materials in the field, weighed the region’s metabolic balance, and looked at the impact of twelve flows if made circular, studying five of them in detail.

According to Aristide Athanassiadis, a co-author of the study, urban metabolism is one of the centerpieces of making a city’s economy more circular, as it goes beyond simply tracking flows. “Measuring the entering and exiting flows is not enough,” the co-founder of Metabolism of Cities and Chair of Circular Economy and Urban Metabolism at Université Libre de Bruxelles contends. “You need to understand the systems of your city much more in-depth than that. You need to understand who is consuming, where we are consuming, why we are consuming, and what the drivers are behind the consumption. Therefore urban metabolism really adds a systemic understanding to the flows.”

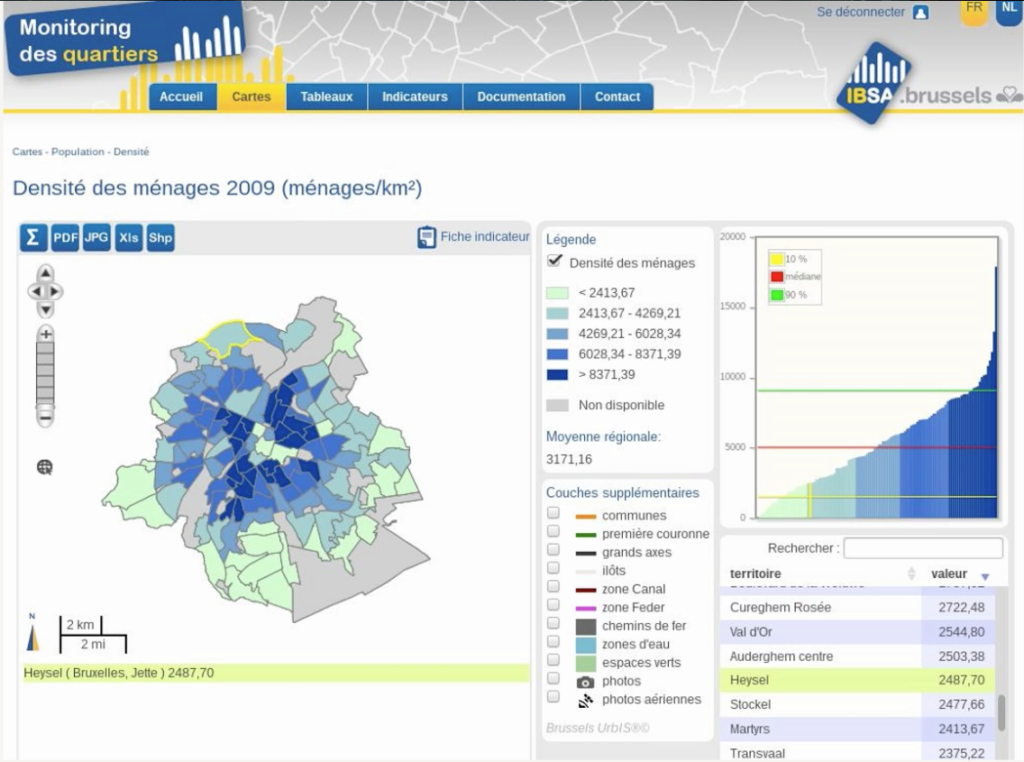

What makes Brussels such a good candidate for in-depth urban metabolism analysis and visualization is the availability of good data on both the regional and local scale. Its statistical office, the Brussels Institute for Statistics and Analysis, collects and provides data at regional, municipal, and even smaller scales, providing insights into important socioeconomic, territorial, and environmental aspects of its urban systems. In the case of energy use, for instance, the office has data at the regional scale that dates back 40 years, supplemented by more recent municipal data made available through annual reports of grid operators and environmental reports. In the case of water, it’s possible to track municipal use as far back as 70 years thanks to data from archival utility reports.

Data visualizations by the Brussels Regional Statistical Office

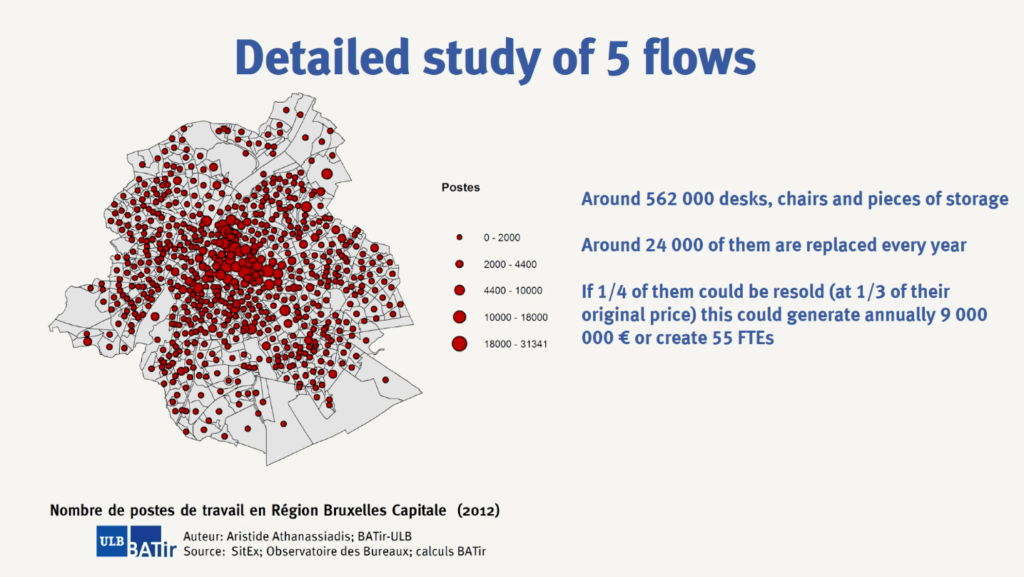

While energy and water data are relatively easy to come by due to built-in metering devices used by grid operators and water suppliers at the source of consumption, the most challenging flow to document and track for a region like Brussels is materials. With no centralized utility manager to measure and collect data as well as a lack of an accounting methodology for transported goods, there is very little detail about what type of materials enter or leave the region.

However, as the Metabolism of the Brussels Capital Region study shows, a detailed analysis of material flows is quite feasible with the proper amount of research and innovative thinking. Studying the material flows of the arts sector, industrial waste, the valorization of local forestry operations, and two flows from tertiary buildings as applied to Brussels’ stock of office buildings, Athanassiadis was able to estimate the economic and environmental benefits of making these flows circular.

Athanassiadis believes that in order to move beyond the current economic system and practices, innovation will be key. And to get that kind of critical mass that can drive innovative thinking, awareness about why it’s so important to reduce consumption and move towards a more circular economy must be raised across all different levels of training.

“We need to combine both the national and local scale in our approach to circular economy,” he says. “Thinking about the types of local companies or trainings we should have will automatically bring in new jobs. Likewise, defining new sustainable consumption patterns will automatically reduce the environmental footprint and create new types of jobs to implement those goals. I really think that if we address this question of consumption correctly it will also have a huge impact on our quality of life and the values that we have for our society.”

This article is part of a blog/vlog series about urban metabolism and its utility in city planning and management while shifting resource flows from linear toward circular. As part of UN Environment’s Global Initiative for Resource Efficient Cities (GI-REC), these educational posts and videos produced by Ecocity Builders in coordination with the Sustainability Institute, urban Modelling and Metabolism Assessment, and Metabolism of Cities, seek to equip city managers and practitioners with the tools and know-how to build and transition towards low-carbon, resilient, and resource efficient cities using integrated systems approaches such as urban metabolism.

Pingback:Urban Metabolism, Part 3: Transitioning Towards A More Circular Economy in Brussels, Belgium – GI-REC

Posted at 05:49h, 09 August[…] Originally posted on: https://ecocitybuilders.org/the-urban-metabolism-of-brussels-belgium-transitioning-towards-a-more-ci… […]